Ukraine’s crop shipments are being throttled, even before the latest negotiations over extending an export deal that’s provided farmers with a vital outlet after Russia’s invasion.

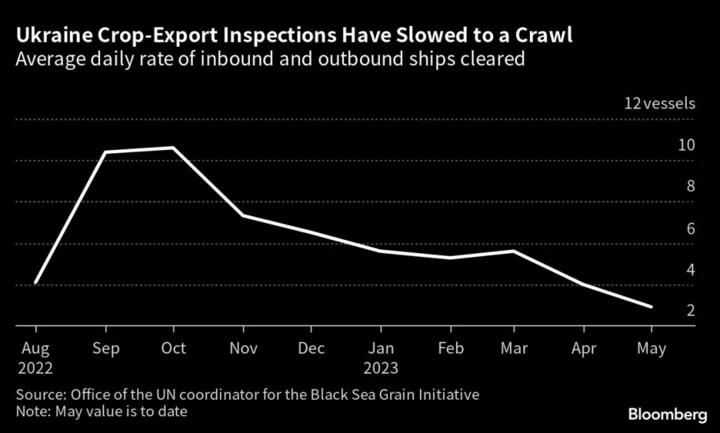

Vessel inspections have been repeatedly disrupted, leaving grain flows through the Black Sea lagging behind previous months. That’s adding to restrictions on cargoes bound for eastern Europe, which is hampering sales ahead of the next harvest.

“Many farmers and big agricultural producers are concerned about their ability to export their grain and oilseed products because we see these issues on both sides,” Roman Slaston, chief executive officer of the Ukrainian Agribusiness Club, said by phone.

Just two months since its last renewal, the safe-corridor deal is hanging by a thread, with Russia threatening to withdraw on May 18 if its demands aren’t met. That would deal another blow to Ukraine’s farmers and put more pressure on global food prices, unless this week’s Istanbul talks — brokered by Turkey and the United Nations — can help revive the pact.

Officials from Ukraine, Russia, Turkey and the UN are set to start grain-deal negotiations in Istanbul this week, the Turkish defense ministry and Ukrainian infrastructure ministry confirmed.

While crop shipments from Ukraine — a major grains and oilseed supplier — normally slow at this time of the year, the tumult is further denting sales. Export volumes through the Black Sea dropped by more than a quarter in April from the previous month, UN figures show. Uncertainty over the corridor’s extension beyond mid-May is also deterring new contracts and shipments, Slaston said.

Wheat is one of the first crops to be collected, with the harvest usually underway in July. Forward sales so far are scarce, according to the Ukrainian Agrarian Council, which cited analysis from an affiliated cooperative. Offers from Ukraine were absent in a recent tender by Egypt — a top global buyer — for June and July supply.

Russia, the world’s biggest wheat exporter, has said it wants obstacles hindering its own food and fertilizer shipments to be removed as a condition of extending the Black Sea grain pact beyond mid-May. Moscow’s demands have previously included pushing for the reopening of an ammonia pipeline.

“Ukrainian exporters are in no hurry to charter vessels after that date,” Maxym Kharchenko, freight-market analyst at UkrAgroConsult, said in a note.

Ukraine has repeatedly blamed Russia for slowing grain flows. On average, inspections are clearing less than three inbound and outbound crop vessels a day in May, according to the UN, with no checks on Sunday or Monday. Another 62 ships are waiting to move to Ukrainian ports for loading.

As shipments through the Black Sea corridor dwindle, flows by road and rail via Ukraine’s European Union neighbors slumped to the lowest in at least 10 months, according to UkrAgroConsult. Some EU nations are curbing grain imports, arguing that a glut is threatening the livelihoods of their own farmers.

The EU agreed to temporarily restrict key Ukraine crops to only transit through five eastern member states. The two sides are due to set up a platform to coordinate and monitor problems for Ukrainian agricultural exports.

Local farmers are in the midst of corn and sunflower planting, and the trade uncertainty is pushing smaller growers to shift some acres to crops like soybeans, which aren’t restricted by the EU. That could further weigh on shrinking Ukrainian grain output.

“It motivates them to switch even more from grains to oilseeds or other crops, or not invest as much in their production,” Slaston said. “It might lead to lower yields and lower total output.”

--With assistance from Selcan Hacaoglu and Patrick Sykes.