After failing to win over Thai conservatives in his first attempt to become prime minister, things are looking increasingly difficult for pro-democracy leader Pita Limjaroenrat to secure a victory even if he were to try again.

The parties outside of Pita’s Move Forward-led coalition and the majority of military-appointed senators are opposed to his key campaign promise of amending the so-called lese majeste law that punishes anyone for defaming or insulting the king or other royals.

Also, the Harvard-educated politician risks disqualification as a lawmaker after the poll body found him in breach of election rules — saying he held shares in a defunct media company while running for public office. While he may still go for a second chance at premiership when parliament meets next on July 19, analysts expect support for Pita to wear thin within his alliance should he lose again; although there’s no limit on the number of re-votes he can seek.

“I think they will run him again,” said Kevin Hewison, emeritus professor of Asian Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Another attempt by Pita will probably harden the stance of conservatives and only weaken support for the pro-democracy alliance, according to Hewison.

The longer it takes for Thailand to form a new government, the more investors will lose confidence in the $500 billion economy whose expansion has been lagging emerging-market peers in Southeast Asia through the pandemic and after. Political wrangling between pro-democracy and conservative groups have also hurt the country’s stocks, bonds and currency markets.

Here are some other scenarios that could play out:

Pita Supports Pheu Thai

Pita could step aside and instead support his coalition partner Pheu Thai, which finished second-place in the May 14 general election and is linked to exiled former leader Thaksin Shinawatra.

Isra Sunthornvut, a former member of parliament for the Democrat Party, said he wouldn’t be surprised if next week Pita throws his support behind Pheu Thai to lead the government “for the sake of the country and democracy.”

The only challenge to this scenario is that Pheu Thai may find it difficult to muster support from the conservatives while still being an ally of Move Forward, which has refused to back down on its push to amend the royal insult law.

Pro-Democracy Group Splits

That could leave Pheu Thai inclined to consider breaking away from Move Forward’s coalition and try forming a government led by one of its three candidates for the post, including real estate magnate Srettha Thavisin and Paetongtarn Shinawatra, the youngest daughter of Thaksin.

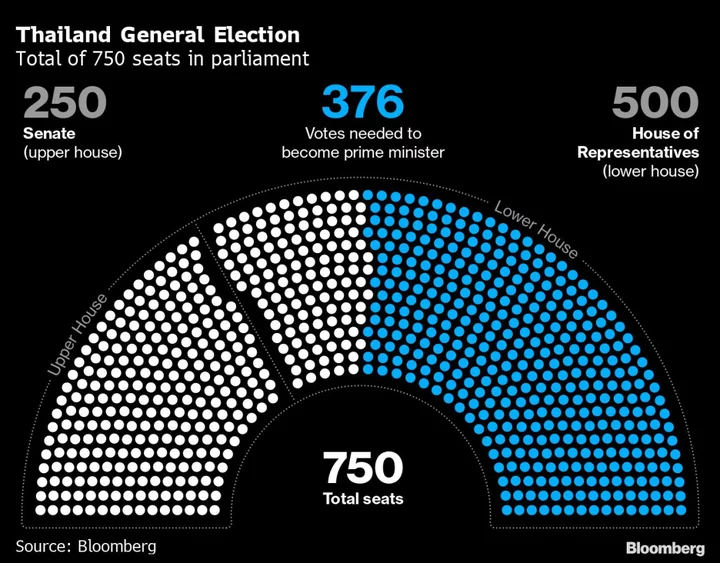

Thaksin, who has been considering returning home, had previously said Pheu Thai would not support any attempt to reform the lese majeste law. That makes it easier for Pheu Thai to win enough support from the 250-member military-appointed Senate, helping put a new government sooner than later.

The private sector wants the new government to be in place as soon as possible, so our economy can continue to grow as expected, Thai Chamber of Commerce Chairman Sanan Angubolkul said Friday.

Military-Backed Minority Government

A third scenario involves the Senate supporting a minority government led either by Bhumjaithai’s Anutin Charnvirakul or one of the military-backed parties. That outcome, however, risks sparking protests by supporters of pro-democracy groups.

Since the Senate’s ability to vote for the prime minister expires next year, any minority government is at risk of falling in a no-confidence vote. To guard against that, it’s possible that the establishment may petition the courts to disband Move Forward as what happened in the past to their predecessor, using the push to amend the royal insult law as a pretext, and even annul the election result.

“But that might take some time,” Hewison said referring to the process of disbanding Move Forward and annulling the result. “That said, going to an election quickly is unlikely to produce a different result. But conservatives in Thailand are a balmy lot.”

However, any move to ban the nation’s popular politicians may lead to massive demonstrations. And this time the risks are even higher for the royalist establishment, as protesters have recently been much bolder in directly targeting the monarchy than in previous years.

Such a turn of events could end up hurting tourism, the only economic engine that’s firing on full cylinders and supporting Thailand’s growth amid a downturn in global demand for goods.

--With assistance from Suttinee Yuvejwattana, Cecilia Yap and Anuchit Nguyen.

Author: Philip J. Heijmans and Patpicha Tanakasempipat