Spirit Airlines Inc.’s top executive told a judge that the low-cost carrier suffered years of pandemic-fueled losses that show no signs of ending, which pushed the company into a merger with JetBlue Airways Corp. that the US government now wants to prevent.

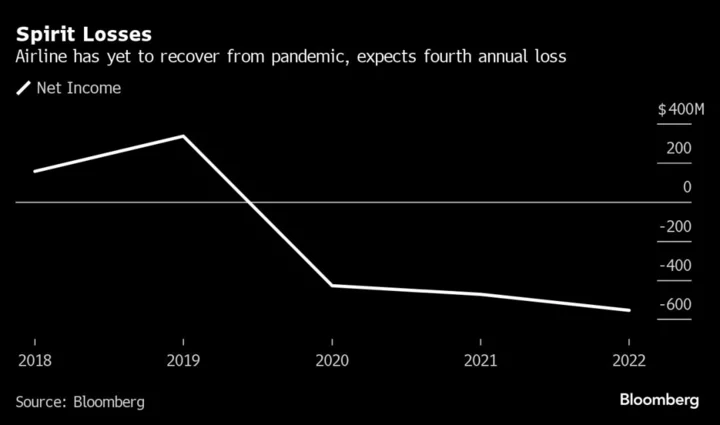

Higher costs for fuel, labor and maintenance compounded the impact of the loss of travelers after the Covid-19 outbreak, and Spirit is on track for its fourth consecutive annual loss, Chief Executive Officer Ted Christie testified Wednesday during the second day of an antitrust trial in Boston. “We’re expecting it to continue to get worse into 2025,” he said.

Spirit’s share of the domestic airline market is “relatively insignificant” at under 3%, even after more than a decade of rapid growth, Christie said. Company executives hoped that accepting a $3.8 billion offer from JetBlue last year would create a company that could compete with the four top carriers, which get 80% of ticket revenue, he said.

“What we’re really trying to do is establish a fifth viable competitor in what is a very dominant space by the big four airlines and in order to do that you have to gain scale,” the Spirit CEO said. JetBlue is the sixth-largest domestic carrier and Spirit is the seventh-largest.

While still ranking well behind behemoths like Delta Air Lines Inc. and American Airlines Group Inc., a bulked-up JetBlue would leapfrog Alaska Airlines to become the fifth-largest carrier in the US.

Read More: JetBlue Cites ‘Staggering’ Delays While Forecasting Loss

The US Justice Department sued last year to block the deal it says would kill JetBlue’s fastest growing competitor in the US and limit choices for passengers, especially in the market for ultra-low-cost air travel. It’s the latest effort to crack down on airline consolidation after decades of lax enforcement.

But Christie said the Spirit-JetBlue combination won’t hurt the market the way the government claims, because “the dynamics of the industry have changed.”

While Spirit helped to popularize the “unbundled” pricing model — tickets with extra fees for things like carry-on bags or snacks — many other airlines now offer that option, Christie said.

“Larger airlines are more effectively competing for our type of product,” which is significantly impacting Spirit’s bottom line, he said.

Still, a merger with JetBlue raised concerns among Spirit executives when it was first proposed. Christie and others were worried the deal wouldn’t get approved by federal regulators, mostly because of JetBlue’s alliance with American Airlines, which was dissolved after a federal judge agreed with antitrust enforcers that the alliance would reduce competition and boost fares for consumers.

Read More: Spirit First Saw JetBlue Deal as Bid to Eliminate Low-Cost Rival

But “there was a path by which we could see engaging in a transaction with JetBlue, and we outlined to JetBlue that path,” which included a stronger commitment to make significant divestitures, Christie said.

The federal government argues that the proposed divestitures, which include slots and gates in New York and Boston, don’t go far enough to restore competition lost in the deal.

DOJ lawyer Aaron Teitelbaum questioned Christie about Spirit’s plans for growth after the pandemic, asking whether executives made a strategic misjudgment to continue growing despite uncertainty in the industry.

“Slower growth would have been more ideal during and coming out of the pandemic,” Christie said. “It looks like we probably outgrew the opportunity right now.”

The trial is being heard by US District Judge William Young without a jury, which means he’ll be the one to decide whether the sale should be permitted to proceed.

The case is US v. JetBlue, 23-cv-10511, US District Court, District of Massachusetts (Boston).