Investors have spent months fretting about everything from South Africa’s daily blackouts to inadequate laws on terror financing and political instability before next year’s elections. Now they have a new concern: geopolitical tensions.

On Thursday, US Ambassador Reuben Brigety accused South Africa of supplying weapons to Russia. The allegation escalated growing tensions over South Africa’s refusal to back the US stance on Russia’s war with Ukraine, and the African nation’s deepening relationship with the BRICS economic bloc. President Cyril Ramaphosa said his government was probing Brigety’s claim and called his remarks “disappointing.”

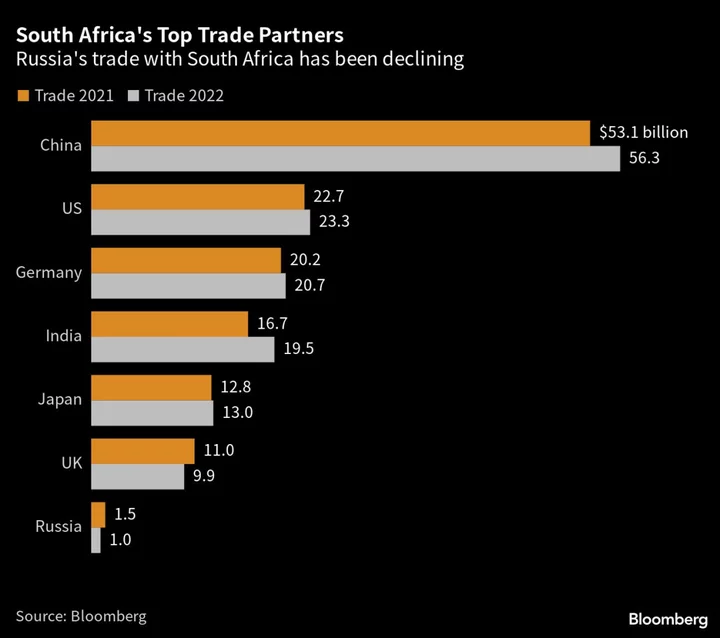

The rand slumped to its weakest level on record against the dollar on concern that any significant deterioration in its relationship with the US — its second-biggest trading partner — may put trade worth billions of dollars at risk.

While President Joe Biden’s administration dialed back its envoy’s hawkish tone and Brigety on Friday sought to “correct any misimpressions” created by his remarks, investor concerns about South Africa’s growing challenges remain.

Many businesses in the continent’s most-industrialized nation have no electricity for almost half each day because of rolling blackouts, known locally as loadshedding. Mining companies and food producers are struggling with the state-owned freight monopoly’s inability to fix logistical constraints, and as many as half of the population of 61 million depend on some form of welfare payment.

“The pressure points that are now coming to a head — load shedding and inferred political alliances — are rippling through financial markets and will increasingly weigh on the economic outlook,” Adriaan du Toit, London-based director of emerging market economic research at AllianceBernstein Ltd., said on Friday “A higher risk premium is clearly justified based on what we know today.”

Even before Brigety’s remarks, South Africa’s political risk had risen to a record while the nation’s economic risk score is at the worst in seven years.

In an effort to prevent the economic and political fallout from worsening, Ramaphosa’s government summoned the US envoy, while the International Relations and Cooperation Minister Naledi Pandor spoke to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken Friday. Statements issued in the wake of both of those meetings didn’t address the veracity of the envoy’s claim.

That may leave investors unimpressed. Foreign direct investment into the nation has remained stagnant, while fund managers are shunning stocks that rely on the domestic economy.

Shoprite Holdings Ltd., which is dependent on South Africa for about 90% of its revenue, has dropped 10% this year. That compares with a 48% gain for local billionaire Johann Rupert’s Cie Financiere Richemont SA, the luxury-goods maker that sources most of its revenue from Asia and Europe.

Meanwhile, AngloGold Ashanti Ltd. is speeding its retreat from South Africa, where the gold miner was formed more than a century ago, with plans to list in New York and make London its new headquarters.

“It does seem that South Africa continues to shoot itself in the foot, with many of the current issues self-made,” Michele Santangelo, a portfolio manager at Independent Securities in Johannesburg. The recent news reinforces the firm’s investment strategy, which is to have a “strong bias towards offshore investments and rand hedges,” he said, referring to investing in companies that make most of their revenue overseas.

‘Maybe I am Crazy’

Still, the volatility may entice some fund managers.

“I still like South Africa, maybe I am crazy,” said Ray Zucaro, the Miami-based chief investment officer at RVX Asset Management LLC. Zucaro said he wasn’t “panic selling” and hadn’t reduced his South African bond and rand holdings. He would consider adding if some of the noise around the US accusations died down.

Relations between South Africa and the US have soured over Pretoria’s insistence that it’s taken a non-aligned stance toward Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The former Soviet Union supported South Africa’s governing African National Congress during the decades-long struggle against apartheid and the party has maintained ties to Russia’s current leaders since the end of White-minority rule in 1994. Ramaphosa spoke to Russian President Vladimir Putin to discuss the “strategic relationship” between the two countries, the Kremlin said on Friday. It made no reference to the controversy over Brigety’s remarks.

The government’s stand on the alleged arms shipment alienated even local companies. Business Unity South Africa, a lobby group, said the administration’s response has been “unsatisfactory as it introduces uncertainty that we simply cannot afford.”

--With assistance from Colleen Goko, Paul Vecchiatto and S'thembile Cele.