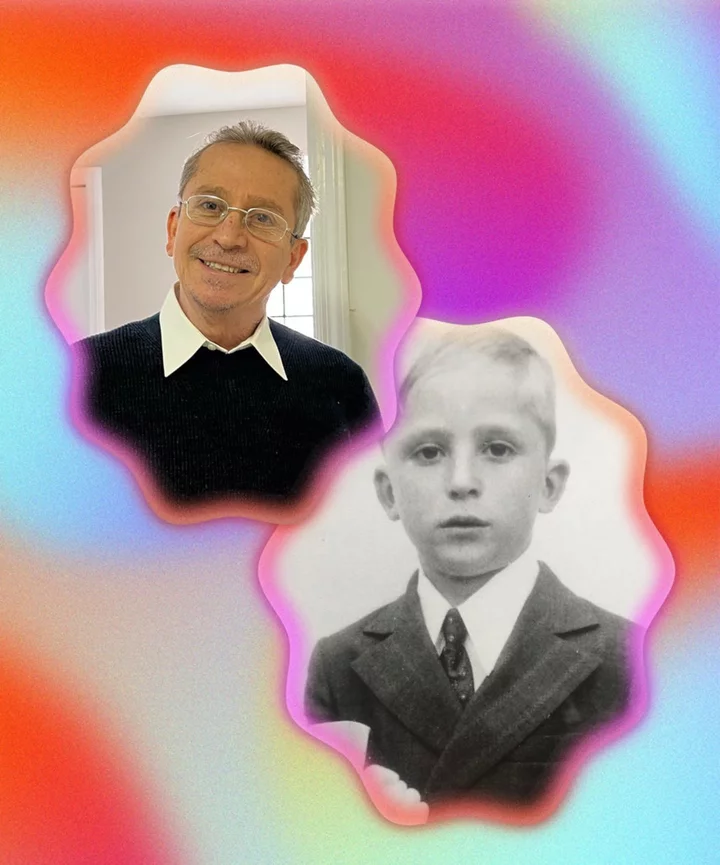

If you crack open the mountains of Antioquia, Colombia, you’ll find my father’s inner child conserved in its stone. Before I left Medellín after almost two years of living there, I spent some time in my father’s pueblo, Montebello. After a day at a friend’s finca, the sun setting in a warm blue over the mountains, I looked into the valley and pictured my father as a child, standing in the same spot. He would have probably been riding horseback, a chestnut horse named Morgan who he’d always tell us stories about, gazing over the valley and dreaming about a life beyond the mountains. My entire life I’ve seen remnants of my father’s inner child peeking out from inside him: in the way he laughs; the way he’d play with my siblings and me, having just as much fun as us; the way he’d cry for his mother; the anger and resentment he held at the way life played out.

My dad left Colombia in 1985 at 21 years old and landed in Miami before making his way up to Queens, New York. When I look at photos of him from this time, I can see the hope and excitement in his eyes. He’d work in kitchens as a dishwasher, manage a dangerous bar in Queens frequented by members of the cartel, struggle to learn English, have lots of money, lose lots of money, and be the only person to tell himself to keep going.

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, calling Colombia wasn’t as easy as buying a calling card or dialing +57 [insert phone number] through WhatsApp. For months or even years on end, his family would wonder where he was or if he was even alive. Today, Papi is 59 years old, the owner of a contracting company, a husband, and the father of four children. When I see him sitting in the living room at night, after a long day of work, I see those same eyes from the photos, now with blossoming age spots around them, and wonder where the boy who rode horseback through the mountains has gone.

“For my father and so many migrants, coming to the U.S. comes at the expense of their inner child, who held so many dreams, so much magic, and so much hope for the future. Often, that inner child had to be sacrificed to ensure the rest of them survived.”

Natasha LópezAccording to clinical psychologist Dr. Rosanna Lora, there are at least four aspects of the immigrant experience that can affect one’s inner child: arrested development, which occurs when a migrant’s emotional growth is stunted due to the stress and trauma of immigrating; straddling two cultures, and the feelings of being ni de aquí, ni de allá; the parentified child, where the child takes on adult responsibilities to support themselves or their family; and feelings of fear, guilt, and shame that arise from the challenges and stigma associated with being an immigrant.

“The migration process is scary, and I think people forget we have inner kids within us and they think, ‘Oh, I should have known this’ or ‘I should know how to feel,’” Lora tells Refinery29 Somos. “But, if that child has been traumatized, they’re trying to make sense of the world. So now here you are, an adult trying to figure things out that probably impacted you as a child.”

For my father and so many migrants, coming to the U.S. comes at the expense of their inner child, who held so many dreams, so much magic, and so much hope for the future. Often, that inner child had to be sacrificed to ensure the rest of them survived. Below, four Latinas share their experiences migrating to the U.S. as children and young adults and how that experience affected their relationship with their inner child.

Vianney Harelly, Poet and Writer, Mexico, She/Her

From sixth grade through high school, my sister and I went to school in the U.S. but still lived in Tijuana, Mexico. We would cross the border every single day and wake up at three or four in the morning to make it in time for school at 7:30 a.m. I wrote a poem in high school called “ser Latine en dos mundos.” The feeling I had crossing every day was like changing identities daily. I felt I left a little part of me back home each day — the moment I crossed the border, a part of me was left in Tijuana, in Mexico. It kind of altered my sense of self and identity.

Before crossing and getting to the Border Patrol, our parents would prepare us and tell us what we had to say. “You’re here for the weekend” or “You’re here visiting, but you also live over there with your uncle and you stay once in a while,” they would tell us to say. They would prepare us for it because saying the wrong thing at the border could cost us our education. I would just get so stressed at the border. It’s no surprise that in middle school I started experiencing alopecia.

“I’m trying to heal my relationship with my city and my country as I’m healing my inner child. When I’m in Tijuana, the anxiety comes back. It’s like my body knows I went through a lot of traumas in my city.”

Vianney HarellyI see my inner child as being someone who is always stressed and very anxious. It wasn’t just having to go to school in another country. My parents were also fighting a lot and a lot of things were going on in my family, which added to that anxiety and stress. In my poem “ser Latine en dos mundos,” I talk about not knowing who I am or what to tell people when they ask me, “Where are you from?”

I see myself now as someone trying to heal that inner child, having my books published, having a bachelor’s degree, and doing all these things for myself and my inner child. But I also feel very sad for my younger self, who was struggling in that car crossing the border and trying to adapt. I’m trying to heal my relationship with my city and my country as I’m healing my inner child. When I’m in Tijuana, the anxiety comes back. It’s like my body knows I went through a lot of traumas in my city.

As immigrants, we learn from an early age about not having a sense of belonging and thinking that we have to choose one place as home when we could have many places that we call home. I guess it’s just part of my identity now: not knowing where home really is and not forcing myself to choose.

Mónica Hernández, Artist, Dominican Republic, She/They

I was born in Santiago, Dominican Republic. I moved to New York when I was six years old in October 2001. I was a really easy child to deal with, but I think it was because of my hyper-awareness of what was going on — whether there had been a big change and I needed to be helpful or I just needed to be quiet.

When I think about my childhood, I remember it a lot in terms of how I felt and what I felt was guilt. I remember feeling bad or guilty about something, like I was doing something wrong. When you’re from a marginalized background, you’re raised with so much fear. I have had to do a lot of work to undo the fear I’ve been raised with — that’s what guided a lot of my parents’ behaviors. Everything was cast in a negative light, from my desire to make art to wanting to go outside. It was very hard for my family to see me as my own self because the world outside was scary.

“I wish I would have had more support. I wish it would have been different. That’s a really hard thing to desire because it feels like it’s invalidating all the work your parents did. It’s hard to look back on it and think my inner child would’ve definitely benefited from something different.”

Mónica HernándezPart of the reason I paint a lot of interiors is because my life was spent indoors. As a child and as a teen, I was very limited in my ability to go outside. I kind of tend to have the domestic as this space that’s like home, but it’s also kind of constraining. With my memories, my inner child, and my inner teen in my work, it’s ultimately an attempt to feel seen. But it’s also an attempt to explore what all this meant and to reflect on what it was like to be indoors so much. I always felt very detached from existence. My memories are of thoughts; they’re not of activities, actions, or experiences. I always felt this detachment from myself. I lived in my brain.

For a lot of the work I originally started to make in college — when I was trying to learn how to paint — I would take photos of myself as references. It was my attempt to see myself because I had no body awareness. My entire life was lived in my head. Ultimately, one of the feelings you get when you are an immigrant or you go through these major shifts in location is that you’re taken outside of yourself.

I wish I would have had more support. I wish it would have been different. That’s a really hard thing to desire because it feels like it’s invalidating all the work your parents did. It’s hard to look back on it and think my inner child would’ve definitely benefited from something different.

Paula Fernandez, Student, El Salvador, She/Her

One of the most prominent memories I have is having to say goodbye to my mom’s best friend. She was always there. She helped raise us and was such a good friend to my mom. She had a big impact on me. When we had to say bye, I started crying because that’s when I started understanding we were not coming back to El Salvador.

The next thing I know, we’re arriving at my current apartment where my family lives, my grandparents, my aunt, and my cousin. They had made a room for the three of us to sleep in. I entered third grade, and the school system in New York was very different from the system in El Salvador. There are different grades, different tests, and, of course, a whole different language. I became obsessed with learning English to the point I ended up forgetting my Spanish. I felt like I had to do well in school because there was no other option. That was the whole point of coming here. The point was to have an American dream. How am I going to do that by paying my mom back with bad grades?

“As an adult thinking back on my childhood, I feel sorry for myself because I ended up putting so much weight on my shoulders. … I do wish some things could’ve been different because now, as an adult, it has translated into different parts of my life, like developing stress and not being able to process some emotions and memories.”

Paula FernandezAs an adult thinking back on my childhood, I feel sorry for myself because I ended up putting so much weight on my shoulders. I think about things I should not have been worrying about at that age. I do wish some things could’ve been different because now, as an adult, it has translated into different parts of my life, like developing stress and not being able to process some emotions and memories. I recognize some reactions I have today come from things I learned back then.

I truly grew up too fast. I put the responsibility on myself of having to take care of myself. I have been healing my inner child by making sure I make time for myself. I take my time with things; I try not to stress. I have not been back to El Salvador since I left 12 years ago, but I am heading back this month. I’m looking forward to seeing my family again, but unfortunately my mom’s best friend passed away before I was able to see her again. I’m very excited to be part of my culture and celebrate all the things I was raised with once again.

Adriana Urbina, Chef, Venezuela, She/Her

I moved to New York when I was 19, about to turn 20. It was not in my plans to leave because I love Venezuela, but due to the political situation, things got very dangerous. In Venezuela, working in a kitchen as a chef, it was easier to express myself, to really ask for what I needed. But when I moved, everything was so different: the language, even the kitchen setup was totally different. I had to learn from the bottom-up, and it was very difficult. I was excited, but at the same time, I was very frustrated because I had pressure on me to make money. My parents didn’t have the money to support me. I also wanted to work for them. I had no other option but to succeed.

The first day I worked in a kitchen was terrible. I felt like an outsider. They were yelling at me, and I was not able to express myself, so they immediately told me to get out of the kitchen. It was so frustrating because I had experience and I knew what I was doing. But because I couldn’t communicate, they just cut me. That was a breaking point. I wanted to quit and leave; but on the other hand, I still wanted to prove I can get better at what I do.

“I’m finally healing and bringing that inner child back to life. My first baby, who was born last September, is part of that, connecting with my childhood again and trying not to be so serious.”

Adriana UrbinaDuring that time, I had to focus all my energy on working. I didn’t have time for fun, to bring my inner child to light. I was 19, and my priority was work. I didn’t care about anything else but work. Thinking back now, I feel like my inner child was forgotten. I’m finally healing and bringing that inner child back to life. My first baby, who was born last September, is part of that, connecting with my childhood again and trying not to be so serious. I used to think that if I’m serious, I’ll succeed. I know now that’s not the case. If you connect with your inner child in everything you do, things work in a more beautiful way. I understand that now.

Cooking is an activity I started when I was very little. I thought of it as a game because it was fun and brought out a really beautiful energy in me. So now I try to think about my work as a game, like play more than something rigid. I think about the things I loved to do when I was a child and connect with that energy. When I do those things, I see everything differently. I don’t take things as personal. It’s more fun; everything is more beautiful.