Hong Kong’s bid to wipe a controversial protest song from the city’s internet is flashing fresh warnings signs for businesses that the once-freewheeling international hub is tracking closer to mainland rules.

The city’s High Court on Friday heard the government’s argument for why it should be illegal to perform or broadcast Glory to Hong Kong with criminal intent. That case has raised fears Western tech firms such as Alphabet Inc.’s Google, which has already quit China over censorship, may be forced to reconsider their presence in the city. Many versions of the song have already disappeared from online platforms such as Apple Inc.’s iTunes and Spotify Technology SA.

Government prosecutors argued the tune’s proliferation online was a matter of national security that would plant seeds of secession, an offense under a Beijing-drafted law carrying sentences as long as life in prison. The judge set a July 28 date for handing down a decision.

The government’s determination to pursue the ban shows its campaign to eliminate dissent is still expanding. That’s despite a three year-crackdown under the China-imposed national security law that’s put the city’s political opposition either behind bars or in self-imposed exile, and shuttered the most-critical media outlets. Spotify and Meta representatives declined to comment, while Google and Apple did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

In another sign of that expansion, Hong Kong authorities this month announced HK$1,000,000 ($127,650) international bounties for eight activists living abroad, casting the net wider on attempts to police government critics. The US State Department condemned the “extraterritorial” application of the warrants and rewards.

Hong Kong’s liberal institutions, legal system and capitalist markets for years were the foundation of its status as a global business hub. This week’s court case is the latest sign those pillars and the city’s prized free speech are being eroded. The UK has already pulled its top judges from the city’s highest court over human rights concerns.

On Friday, a lawyer appointed by the court to argue the case against the government reiterated that banning the song could harm the rights of individuals, was unnecessary given existing legislation, and would be difficult to enforce with companies based in Silicon Valley.

“The potential injunction shows the increasingly blurred lines between the national security sphere and other spaces,” said Thomas Kellogg, executive director of the Georgetown Center for Asian Law.

“International businesses operating in Hong Kong need to take note: They could be drawn into NSL enforcement at any time, which presents very real reputational risks and costs,” he added.

The city’s national security law offenses “are clearly defined and are similar in many ways to the national security laws of other jurisdictions,” a government spokesperson said in a statement to Bloomberg News.

The implementation of the law “restored stability and increased the confidence in Hong Kong, thereby allowing the city to resume its normal operation and the prestigious business environment to return,” the statement said.

The High Court on Friday will examine an injunction submitted by the government last month that would make it illegal for anyone with criminal intent to perform or broadcast Glory to Hong Kong, including the lyrics and melody.

Authorities also cited 32 videos of the song on YouTube in their filings to the court. While it’s unclear how tech firms will respond if the court grants the injunction, Google has previously said it will not remove web results “except for specific reasons outlined in our global policy documentation.”

Xiaomeng Lu, a director at Eurasia Group who specializes in geopolitics and technology, said if the song is banned it could deter foreign investors.

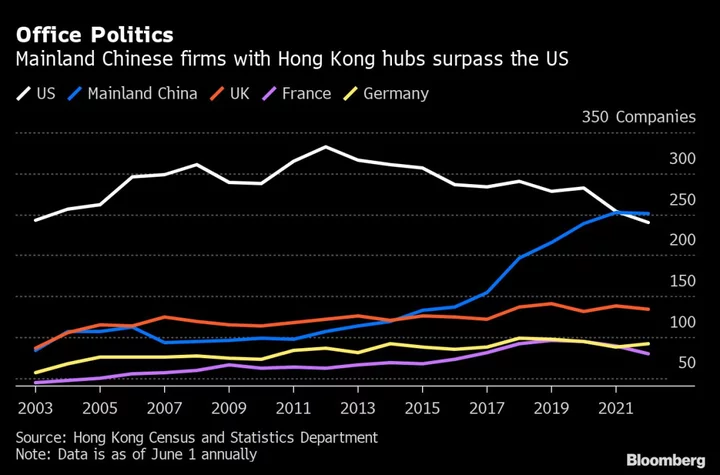

“Hong Kong’s information environment is gradually syncing up with that of mainland China,” Lu added. “Hong Kong is transforming from an international business hub for everyone to a global gateway for Chinese companies.”

Last year, mainland Chinese firms with regional headquarters based in Hong Kong outnumbered American ones for the first time in more than three decades. A 2022 survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong found that 8 in 10 businesses reported feeling effects from the security law, including lower staff morale and the loss of talent.

In another sign of strengthened ties with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s government, the city announced earlier this week that Beijing had appointed a former top spy official to oversee the city’s national security office.

The security law, along with China’s regulatory crackdowns, have even made having frank conversations about economic topics hard, more than 30 analysts, fund managers and executives in or connected to Hong Kong last year revealed.

Years of harsh Covid controls imposed in line with strict mainland policies also undermined business confidence. The city flip-flopped several times on pandemic policies and was one of the last places to lift mandatory quarantine for inbound travelers.

“International companies and investors are becoming more alive to the risks of doing business in an environment in which policy volatility is increasingly the norm,” said Andrew Yeo, the Asia head of strategic advisory firm Global Counsel.

It’s hard for businesses to know where the “red line” is in Hong Kong now the hub is more closely aligned with Beijing, said one financial professional who moved from Hong Kong to Singapore during the pandemic.

The person, who asked not to be identified, also leaves his personal electronic devices behind when traveling to Hong Kong, something he only used to do when traveling to mainland China.

Some firms want to avoid association with Hong Kong because over the reputational risks of its China ties, according to a business owner who oversees production for multinational brands.

Kristian Odebjer, chairman of the Swedish Chamber of Commerce, said that while Hong Kong still had several “core strengths” its story has become “a more challenging one to tell.”

Any injunction against a protest song that diminishes internet freedoms would likely further complicate that narrative.

“Hong Kong may be back,” Odebjer said, “but it is a different Hong Kong.”

--With assistance from Sarah Zheng and Jill Disis.

(Updates with July 28 ruling target from the third paragraph)